March 2012

Gravity: Your Back’s Best Friend

By: Jason Martuscello

An inevitable addiction has arisen that is plaguing the country and proposing deleterious health effects. Although this silent killer may appear a minor threat to the unbeknownst, research has painted a different, not so pretty, picture. This addiction has been associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, weight gain, colon cancer, endometrial cancer, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, metabolic risk, type 2 diabetes1 and numerous musculoskeletal disorders2. So what is this potential hazard? The answer is sitting.

Although it is becoming more apparent of the health effects associated with sitting, an increased reliance upon the chair in common day workplace as well as in the home environment still exists. From driving the car, operating computers, playing video games, eating meals, and watching television – are just some examples that contribute to a large portion of sedentary behaviors. Although the health effects of prolonged sitting can be detrimental, the goal of this paper is not to convince you not to sit, although it may be beneficial, it is not realistic for the majority. In light of the disparities, there are protective measures that can be adopted for a safer seated environment. Therefore, the goal is to gain an appreciation for “how” to appropriately sit. This in turn will contribute to improved musculoskeletal health.

Why do we sit?

Sitting is routinely performed in order to transfer the weight of the body to the supporting seat. A large proportion of the weight is transferred to the chair through you ischial tuberosities (the bottom portion of the pelvis). Depending on the chair and the posture assumed, weight can also be distributed to the backrest, armrests, and the floor3. In other words, sitting simply expends less energy than standing. Additionally, sitting provides the stability required to perform high visual and motor control tasks3.

Anatomy of Sitting:

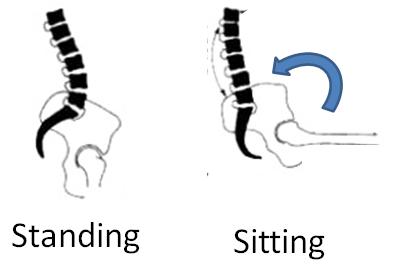

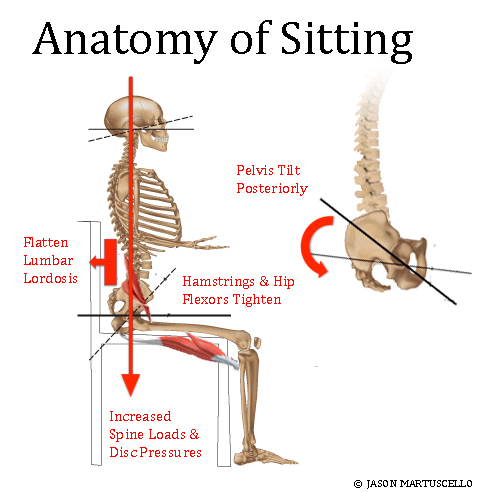

In assuming the seated position, the hips and knees are flexed, the

pelvis rotates backwards, and the lumbarlordosis decreases4. The

loss of lumbar lordosis has been established as a predictor of low

back pain5. Adopting a poor sitting posture can result in overloading

the spine6 through increased loads on the discs and posterior spinal structures7. Slumped sitting will further exacerbate the issue causing increases in disc pressure8.

The muscular system is constantly active in a standing posture to maintain our upright position9. To achieve this posture, cocontractions of synergistic muscles is important to maintain the natural spinal curvatures. Similarly, when sitting, the muscular system is active to maintain our posture but to a much lesser extent, due to the seat bearing weight of the body. A basic ergonomic principle is to minimize the static (constant) muscular activity in maintaining the sitting posture against gravity10. Therefore, muscular cocontractions should exist to neutralize the spinal alignment. Alternatively, insufficient activity leads to a reduced lumbar curvature, and is believed to put reliance upon passive structures including bone, vertebral discs, joins, and ligaments to maintain posture10. Thus, the goal should be to achieve the minimal amount of muscular cocontraction to sustain a neutral spinal alignment to avoid support from passive structures.

Adopting a poor posture in the seated position will result in a cascade of issues degrading the musculoskeletal system. Inadequate distribution of muscle activity will lead to muscular imbalances. Furthermore, activation sequences will be disrupted and movement flaws will likely result (See Muscle Imbalance article for more detailed discussion).

Sit Up Straight - Right?

Contrary to popular belief, sitting up and not utilizing the backrest of chair is not only ineffective but may impose unnecessary strain. The backrest of a chair, as mentioned previously, can be used to transfer body weight (depending on the angle and posture alignment). Research has found backrests will reduce loads on the spine and intradiscal pressure11. The contrary view would argue we challenge the core musculature to a greater extent by not using backrests. Although this may be true, this tends to result in a fatigued posture causing the body to slump forward and decrease our lordotic curvature12. In deciding on the inclination angle, it has been determined that the increase in the inclination (further the recline) decreases the amount of muscular activity13. However, the further the reclined position, the larger the distance from your work space. (i.e. desk, computer). Therefore, a general guideline to transfer the most body weight without sacrificing work environment is to use the backrest inclined between 90-105 degrees3.

Should we use Lumbar Support?

Lumbar supports are designed to restore the natural curvature of the lumbar spine. In a seated posture, lumbar lordosis decreases4 predisposing the body to back pain. The

use of lumbar support has shown to reduce intradiscal loads on the spine14 and restore

the lordotic curve8. An adjustable lumbar support feature is becoming more frequent in

chair designs and many options of lumbar support pads are manufactured to help maintain

better spinal alignment.

Putting it All Together

- Sitting provides stability to perform high visual & motor control tasks

- General Goal: Optimal Sitting Posture = Design of Chair + Posture

- Specific Goal: Seated Minimal Muscle Cocontraction + Neutral Spine

- Utilize Backrest & Do Not Slump Forward (Excessive Kyphosis)

- General Backrest Inclination: 90-105°

- Lumbar supports à Help Achieve Neutral Lordotic Curve

This information addresses the adoption of a seating posture and selecting a chair based on the available literature. It heavily stressed that there is no universal sitting posture that is best for everyone. Due to interindividual variability, the posture and chair should be functionally adapted to the task. Furthermore, a single ideal posture is cannot be maintained indefinitely which emphasizing the importance of the chair that allows safe postural adjustments.

REFERNCES

- Bauman A, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, et al. The Descriptive Epidemiology of Sitting:: A 20-Country Comparison Using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). American journal of preventive medicine. 2011;41(2):228-235.

- Ratzon NZ, Yaros T, Mizlik A, Kanner T. Musculoskeletal symptoms among dentists in relation to work posture. Work. 2000;15(3):153-158.

- Chaffin DB, Andersson G, Martin BJ. Occupational biomechanics. Wiley New York; 1991.

- J Jay K. Alterations of the lumbar curve related to posture and seating. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American). 1953;35(3):589-603.

- Adams MA, Mannion AF, Dolan P. Personal risk factors for first-time low back pain. Spine. 1999;24(23):2497.

- Watanabe S, Eguchi A, Kobara K, Ishida H. Influence of trunk muscle co-contraction on spinal curvature during sitting reclining against the backrest of a chair. Electromyography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008;48(8):359-365.

- Nachemson A, Morris JM. In vivo measurements of intradiscal pressure. Discometry, a method for the determination of pressure in the lower lumbar discs. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1964;46:1077.

- Andersson G, Murphy R, Ortengren R, Nachemson A. The influence of backrest inclination and lumbar support on lumbar lordosis. Spine. 1979;4(1):52.

- Woodhull-McNeal A. Activity in torso muscles during relaxed standing. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 1986;55(4):419-424.

- Watanabe S, Eguchi A, Kobara K, Ishida H. Influence of trunk muscle co-contraction on spinal curvature during sitting for desk work. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. Sep 2007;47(6):273-278.

- Rohlmann A, Claes L, Bergmann G, Graichen F, Neef P, Wilke HJ. Comparison of intradiscal pressures and spinal fixator loads for different body positions and exercises. Ergonomics. 2001;44(8):781-794.

- Bridger RS, Von Eisenhart-Rothe C, Henneberg M. Effects of seat slope and hip flexion on spinal angles in sitting. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. 1989;31(6):679-688.

- Andersson BJ, Ortengren R. Myoelectric back muscle activity during sitting. Scandinavian journal of rehabilitation medicine. Supplement. 1974;3:73-90.

- Andersson B, Ortengren R. Lumbar disc pressure and myoelectric back muscle activity during sitting. II. Studies on an office chair. Scandinavian journal of rehabilitation medicine. 1974;6(3):115.

About the Author

Jason Martuscello, NPI-Certified

Posture Specialist™, is finishing up his M.S. in Exercise Science at

the University of South Florida in Tampa, Florida. He has received his

B.A. from the State University of New York at Plattsburgh. His graduate

research interests include kinesiology, with a specialization in

posture and body alignment. Jason is the Assistant Director of Academic

Relations for the National Posture Institute, in committing to

providing an educational and research based standard in the health and

fitness field. At the University of South Florida, he is a Teaching

Assistant for PET3312 Biomechanics and a Research Assistant. His extra

time is spent volunteering for the federally granted research study in

targeting exercises for preventing back injuries in firefighters. He is

also member of American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM).

|