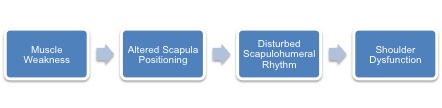

The Upper Core Part I: Anatomical Considerations

Brushing your teeth, combing your hair and

changing a light bulb may seem like relatively simple common household

tasks. However, simplicity can largely be contributed to the intricate

relationship of the scapula and the shoulder complex. Although large

attention is placed on the trunk (core stability) in training,

rehabilitation and performance in other regions, especially the shoulder

complex, often get overlooked. The shoulder complex plays an integral

role in upper quarter function and deserves more attention. A healthy

shoulder complex will allow ease in functional tasks, better performance

in sporting events, and prevention of injuries. In this Part I series

on the Upper Core, essential anatomical features will be explained.

Also, muscles actively contributing to the mechanics of the upper

quarter region will be considered. The importance will be reinforced

through the pathomechanics of the upper core. The Part II series to the

Upper Core will look at activation and maintenance, through

strengthening to provide stability for upper quarter function.

What is the Shoulder Complex?

The

shoulder complex includes the clavicle, scapula, and humerus. The

bones are united through the glenohumeral (GH) and acromioclavicular

(AC), and the sternoclavicular (SC) joints. The scapulothroacic joint

is also included within anatomical descriptions of the upper quarter(1).

Movement

stemming from the upper extremities involves a coordinated interaction

from all the joints. The upper core has unique mechanics that allow

tremendous mobility requiring coordinated and synchronous motion of all

the joints. However, the range of motion is compromised by its lack of

bony or ligamentous attachments from the scapula to the axial

skeleton(2). Due to anatomical architecture, scapulothoracic motion

requires a combination of clavicle motion on the thorax (SC Joint),

and/or further scapula motion relative to the clavicle at the AC

joint(3).

Scapula

The

scapula, often discounted in training programs, bears significant

responsibility in upper quarter function. With numerous muscular

attachments, the scapula work synchronously with the humerus to allow

full range of motion known as scapulohumeral rhythm(4). Through precise

coordination with arm movement, stability is provided for distal

mobility. Another important function is its ability to regulate force

transmission. Through the large range of motion, the scapula prevents

impingement and still allows high force transmission.

Scapula at Rest

The

triangular scapula is a flat bone that lies over the posterior thorax

from ribs two to seven. At rest, scapular positioning is important in a

normal functioning upper core. Altered cervical and thoracic spinal

alignment has been postulated in disrupting the resting position

resulting in muscular weakness, dysfunction, and decreased range of

motion(3). One study demonstrated these changes through measuring

spinal posture and its relationship to angulation of the scapula.

Results showed increased forward angulation of the scapula with the

increased curvature of the thoracic spine (kyphotic curve)(3).

Consequently, it is important to assess scapular position during rest.

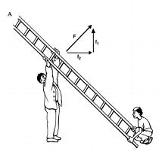

| The

illustration of father and son raising a heavy ladder can be similar to

the relationship of the muscles of the shoulder. The stronger father

will lift and move the heavy ladder while the weaker son will guide it

as it is raised and prevent it from lifting off the ground (stabilize).

The father represents the static stabilizing muscles (serratus anterior,

trapezius, rhomboids) acting as primary movers and the son acts as the

dynamic stabilizing rotator cuff muscles through stabilization. At any

point the father can generate too much power that will overcome the

resistance of the son resulting in instability(1). |

|

Summary

The

four joints including the glenohumeral (GH), acromioclavicular (AC),

sternoclavicular (SC), and scapulothoracic make up the upper core.

Normal upper core function requires coordination between joints.

Muscular attachments including the static stabilizers (rhomboids,

trapezius, and serratus anterior) that provide the movement while the

opposing rotator cuff muscles (dynamic stabilizers) maintain stability.

The force couple relationships properly align the bony architecture

through maintaining posture. Any weakness in the kinetic chain will

create a faulty alignment and predispose injury. Therefore, a static

scapular analysis is vital prior to assessing any dynamic movements.

REFERENCES

- Terry GC, Chopp TM. Functional anatomy of the shoulder. Journal of athletic training. 2000;35(3):248.

- Paine R, Voight M. The role of the scapula. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 1993;18(1):386.

- Culham E, Peat M. Functional anatomy of the shoulder complex. Journal

of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 1993;18:342-342.

- Voight ML, Thomson BC. The role of the scapula in the rehabilitation of

shoulder injuries. Journal of athletic training. 2000;35(3):364.

- Kibler WB. Role of the scapula in the overhead throwing motion. Contemp Orthop. 1991;22(5):525-532.

|